Laughing, crying, tumbling, mumbling,

Gotta do more, gotta be more.

Chaos screaming, chaos dreaming,

Gotta be more, gotta do more.

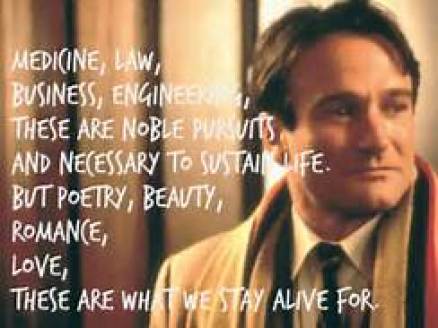

So waxes poetic Charles Dalton, or Nuwanda, in the forbidden poetic caves of The Dead Poet Society. Poetry as a clue to meaning in life? Science has settled everything, or so we have been led to believe, but the poets make their claims:

Or, to answer Tina Turner’s question What’s love got to do with it? the deeper yearnings of the human soul still cry out.

The Medievals understood all of this, anticipating these modern questions, and did so with a poetic flair.